Dedicated to historical and cultural studies about Iran

After Kaveh’s sons were killed by Zahhāk, the blacksmith courageously rose against the tyrant. Leaving Zahhāk’s palace, Kaveh lifted his leather apron upon a spear and proclaimed: “Whoever desires the death of this demonic and oppressive Aži-Dahāka, and seeks the kingship of Fereydun, join me!”

The status of the Kaviani Banner (Derafsh-e-Kāvīānī) in the legendary world of the Iranians is remarkably significant—even astonishing. In Shahnameh, the most important and revered banner of the Iranians is undoubtedly the Kaviani Banner, which may rightly be referred to as Iran’s national banner. Iranians were willing to sacrifice their lives for it, and even their enemies believed Iran’s strength resided in this very flag and sought to capture it.

The concept of humanity and the respect for human rights on a global scale gained far greater attention following the peaceful entry of Cyrus the Great into Babylon. After the peaceful conquest of the city, profound changes occurred across the world. Cyrus the Great’s role in preserving the Iranian world is also significant, as the conquest of Babylon took place only after the Babylonians initiated war against the Persians.

Shahram Goodarzi (the sculptor of the statue of Cyrus the Great) set out on foot from Kelardasht towards Pasargadae on August 26, 2025 (Shahrivargan) intending to arrive there on October 29, 2025 (Cyrus the Great Day). However, on the night of September 16, 2025, he was arrested and returned to Kelardasht.

Mehregan, a festival as highly valued as Nowruz, is an ancient Iranian celebration of love, kindness, and covenant. Rooted in human values, it has endured for millennia, adapting to new beliefs while keeping its essence. Praised by al-Biruni, it also highlights the great role of Mithra in ancient Iranian traditions.

In a recent recitation, many of the great figures of Persian poetry and literature (Ferdowsi, Hafez, Rumi, Nezami, and others) were claimed to be sacrificed in honor of the poet of the verse “From my soul I smell the scent of Karbala at every moment”! Sadly, for years such anti-Iranian and divisive remarks have been repeated in religious gatherings—gatherings often backed by official institutions.

Yalda, one of the most ancient Iranian festivals, celebrates the passing of the longest night of the year and the arrival of longer days, coinciding with the winter solstice. Rooted in both nature and mythology, it reflects Iranians’ deep bond with their environment and cultural wisdom. Despite dynastic changes, religious shifts, and foreign invasions, such festivals have endured, symbolizing resilience and the timeless link between people, nature, and myth.

One major reason Mossadegh, during his premiership, was unwilling to resolve disputes with Britain was that the British insisted the Oil Company should, in some form, continue its operations in Iran. In view of this, Mossadegh turned to a no-oil economy. He had said: “The moral aspect of nationalizing oil is more important than its economic aspect.”

Paradises and Chaharbaghs are among the greatest innovations of the Iranians, with roots in the Achaemenid era, and they had a profound influence on garden design in both the East and the West. It appears that the paradises of the Achaemenids and Cyrus the Great influenced humanity’s vision of paradise itself—so much so that in the myths of various nations, paradise is depicted in the likeness of Iranian paradises. Even in the face of devastating invasions by the armies of the Caliphs and Genghis Khan’s Mongols, Iranian paradises were not destroyed; rather, in the Timurid and Safavid periods they once again flourished.

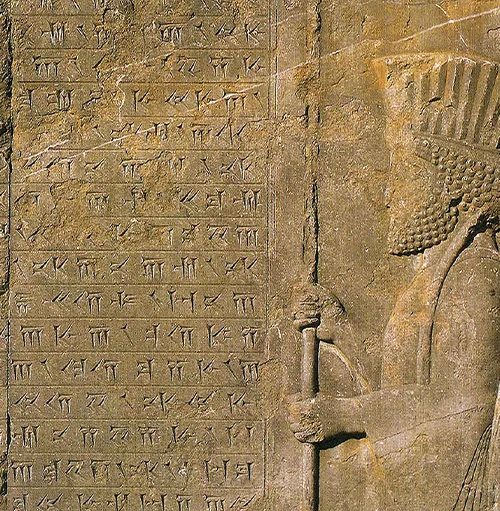

The palace of Persepolis (Parseh) holds great artistic value, as it incorporates the styles of various peoples and cultures. It reflects the cultural policy of its time—an inclusive approach that encouraged all ethnic groups to view Persepolis as their own and to forge a sense of connection with it.